SA73 Public Revenue Without Taxation by Peter Bowman

Public Revenue Without Taxation.

Introduction

It is now widely recognised that the free market system provides a self-organising process that enables a more efficient allocation of a society’s resources than alternative arrangements based on the implementation of pre-conceived plans by central authorities. At the same time the market system offers much greater individual economic freedom and the opportunities for individuals to fulfil their potential in society.

In a free market, transactions are voluntary and are undertaken between a willing buyer and a willing seller. There are many independent buyers and sellers who can compete on quality of service and price. Prices are the outcome of the law of supply and demand, and the overall outcome under a prevailing set of conditions is a condition of stability and optimal allocation.

And yet, when it comes to the provision of public services, which in a modern economy can account for around half of the total economic activity, an entirely different mechanism is used which in many respects is the antithesis of the market system. Goods and services are often made freely available and corresponding costs are met mainly by taxation: “a compulsory contribution imposed by a public authority, irrespective of the amount of service rendered in return”.[1] For these services there is now no willing buyer or seller, no competition and no price mechanism. If one traces back the origins of these arrangements and, in particular the varied and complex methods of taxation employed to collect revenue required to pay for the services, it is found that they are rarely due to the application of sound economic principles and more often are the result of short term political expediency.

A century ago, when government expenditure and corresponding taxation amounted to around 10% of GDP these mechanisms may have had some impact but did not dominate the way the economy operated. Now they have grown to such an extent that the distortions on the market mechanism are so great that it can no longer operate in the way intended and the desired outcomes of the market system are no longer obtained. An unintended consequence is the growth of the proportion of the population, both the most wealth and the least wealthy, that have become dependent on the state.

Strangely, given the superiority of market mechanisms, there is a rather passive acceptance of this situation. Questions about taxation are often limited to the effects of small adjustments in rates, special provisions and how to deal with the complex mechanisms of avoidance and evasion. The overall effectiveness, validity and desirability of the basic process of financing of government services through arbitrary levies is rarely questioned. Yet if the market mechanism is so much more effective at efficiently distributing society’s resources surely the question that needs to be asked is why is it not used for the supply of public sector services as well as private sector ones?

The Effects of Conventional Taxation

Before considering the possibilities of using market mechanisms to govern the supply of public services, let us first consider the effect of conventional taxation on the market economy. Taxes do much more than supply government with revenue. They have a huge impact on the way that economic players behave. For example, a levy of 15c per bag on plastic bags introduced in Eire in 2002 decreased plastic bag usage by around 95%.[2] That outcome indicates the sensitivity of behaviour to the imposition of arbitrary levies. Taxes intended just to raise revenue are going to affect behaviour just as much as those directly intended to change behaviour.

In the UK the incidence of taxation falls to a large extent on employment. This has a huge impact on employment patterns the extent of which is rarely recognised. The nominal income tax rate of 20% disguises the full impact. Take the example of an employee earning a gross salary of £25,000 pa, just below the average for the UK. What goes into the employee’s bank account and is available for them to spend is £20,174. To provide this, taking into account employer and employee’s national insurance as well as PAYE, will cost the employer £27,331 pa i.e. 35% extra.

To put it another way, for every three employees an employer takes on at around the average wage they have to send to HMRC an amount that would pay for a fourth worker. Or one could say that to be worth being taken on and given a take home pay of £20,000 pa an employee has to be able to add over £27,000 pa of value for their employer.P BowmanThe End of Taxation 2

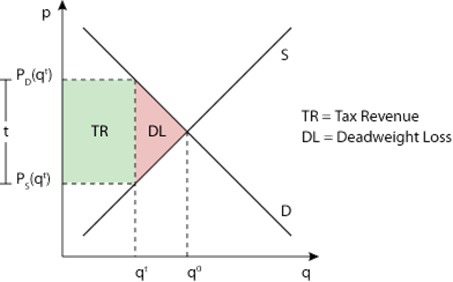

This analysis indicates that income tax hugely inflates the cost of labour and thus distorts the relative cost of labour and capital, disadvantaging labour-intense and service-rich industries compared with those that are capital intensive. This in turn introduces huge distortions into the market mechanism determining the equilibrium between supply and demand. This is represented by a deadweight loss in the supply and demand curves (see figure 1). Conventional theory explains how both buyer and seller lose out, but to different extents depending on the relative elasticities of supply and demand curve for any particular product.

figure 1: Representation of deadweight loss of taxation on supply/demand curve

All that has been said so far is not quite the full story because when the employee comes to spend their salary a considerable portion goes on indirect taxation, ONS data indicates that the top 20% of earners paid about 14% of their disposable income in indirect taxes, of which the main one is VAT, whereas the bottom 20%, the lowest earners, paid about 31% of their disposable income in indirect taxes. [4]

VAT at 20% effectively inflates the retail price of goods and services by 20% distorting both supply and demand but overall reducing the equilibrium quantities sold in the market by a significant amount. As a particular example, let us take the restaurant sector. As a trade with a high service component it is already affected by the high taxes on employment. In addition, all restaurant prices are inflated by 20% by VAT.

Suppose our employee takes his family out for a meal and the bill is £50. Without VAT it would be 20% less, and without PAYE for the restaurant staff, less still, say £33. To supply their employee with that £50 will cost the employer around £67, that is around double what the meal would have cost without these taxes. This is a simplistic example, but it gives an indication of the weight of the burden of conventional tax that hangs around the neck of our economy and the possibilities of greater freedom and prosperity that it now prevents.

Taxation and marginal businesses

These high taxes raise the bar considerably for what constitutes a viable business. It is not sufficient for costs to be covered and a modest return to be made. A considerable arbitrary contribution to pubic revenue is also required. These taxes are applied equally over all regions. They impact most heavily at the margins. How many businesses, that would be viable if they just had to cover costs with sales income, are not viable with the burden of taxation (particularly PAYE and VAT), and how many opportunities for enterprise for small businesses does this deny?

There is a geographical aspect to this burden. For some regions it is much easier to do business than others. The prosperous south-east for example has many economic advantages over other parts of the country, not just geographical but also because of the presence of a prosperous community with disposable incomes. Since this is given no consideration in the way taxation is levied, the most disadvantaged regions are taxed at the same rates as the most prosperous. This has a significant impact on regional prosperity. It is also easy to see how high labour costs have led to the drawing in of migrants prepared to work for the net-value of highly-taxed wages on offer in certain regions and that has given rise to associated social issues.

There is a third accepted reason for general taxation in addition to collecting revenue and adjusting behaviour, and that is to redistribute wealth. This use is based on an admission of failure. Its basis is the acceptance that the present system is unfair and leads to unacceptable distributions which then need to be realigned. It is not a fundamental requirement of public provision and if the preliminary distribution was equitable would not be necessary. One can see that by burdening enterprise with heavy taxation, to pay in considerable part for the redistribution of wealth, this may even be making the situation worse. If people were simply given the freedom to work and receive the full product of their earnings much of the social provision would not be needed.

Public and Private Goods

In a modern economy government provides a range of services. For which of these they are the most suitable provider, and whether there are services which are at present in the private sector which would be better provided by government, is as much a matter of politics as it is economics although there are certain services which Adam Smith described as “the necessary function of government” – defence, law and order which almost all would agree fall to the state.

From an economic perspective, a distinction can be made between public and private goods. These are not necessarily those provided by the public and private sectors respectively. The economic distinction is that public goods can be traded by individual market transactions in that there is a well-defined commodity or service and a well-defined recipient. Public goods are those which cannot be the subject of an individual transaction of which a simple example is street lighting. It is available to anyone who comes into the area in which it is provided. In addition, partaking of the service does not diminish it. Such a service is not going to come into existence without the impulse of some central organising authority.

On more careful examination many public goods – a legal service, health service, education, transport systems, library service, emergency services actually have the characteristics of both types of good. Take for example a road system. There are individual travellers who make use of it but there is also a benefit to the whole economy and many businesses benefit from the presence of the system without actually using it directly. To attempt to cover the cost of a transport system by charging individuals would not only not be viable, it would be unjust and also inefficient. High charges for the service would diminish its use and the whole economy would suffer. Similar arguments could be applied to other services.

The perceived difficulties of using market mechanisms to pay for public services have led even the most liberal thinkers to the assumption that despite all its injustices, its negative impacts on the economy and it being antithetical to the market mechanism, taxation, i.e. the imposition of arbitrary levies, is the only way to pay for these services.

Public and Private Components of Property Values

However, some have recognised that there is another way and it is time to give them a voice. In recent times one of the most original thinkers in this respect was the English economist Ronald Burgess who presented his thoughts in a book with the compelling title Public Revenue without Taxation,[5] from which the title of this essay is taken. Reviewing the writings of the early Neo-classic economists, Burgess rediscovered the key insight of Alfred Marshall that public works and other public outlays create externalities that are manifested in enhanced land values. This points to a way of quantifying and thus providing a market mechanism to pay for public services.

What appears to be the market price of land is in fact a measure of the market price for those public goods and services to which that piece of land provides the occupier with free access to.

What is loosely described as owning property is, more precisely to have property rights over a piece of land. When analysed more carefully this can be seen to have two distinct parts which can be regarded as a private value and a public value.[6] The private value is that part of the market value a willing buyer will pay a willing seller for all the improvements, particularly buildings, which have resulted from work and direct outlay on the site. These improvements are properly called private and conform to the idea of private property.

The public value of freehold property rights over land is that part of its current market price a willing buyer is prepared to pay a willing seller for the net external economies, advantages and other benefits the occupier expects from the occupation and use of the land. It was what Alfred Marshall called the “situation value”.[7] This public value would be equal to the total market price less the value of the improvements.

One example of how this operates, that is familiar to most, is the effect of infrastructure, such as new transport links, on property values,[8] and also the way that there is a premium on residential property in the vicinity of good schools[9].

Using the public component of property values as a basis for public revenue

Given that the public value is due to the actions of the community as a whole, and particularly the provision of public goods and services, it should naturally fall to the government, which represents the community as a whole, as a source of public revenue. How this could work in practice is that those who wish to occupy land to live or work on would need to pay the government to do so. This could be by taking out a lease for an accepted period of say 75 years, or much more effectively, by paying an annual charge proportional to the market value of the public component of the property occupied. The latter would be much more effective since the payment would vary with the increase or decrease in provision. A direct benefit of this arrangement would be that it could enable the financing of public investments such as new transport links. They could effectively become self-financing. With the provision of a new transport link the associated uplift in land values would now fall to the provider rather than the owner of the land. The anticipation of the uplift could provide the collateral for the financing of such a project. Conversely, with the arrival of new developments that have a negative effect on location values, such as the installation of an incinerator, those in the locality would be compensated by reduced payments. There would be much greater democratic accountability. Communities could vote for increased services with corresponding increased payments or for a decrease in services with a corresponding decrease in payment.

Generally, the law of supply and demand could now operate in the field of the provision of public services. Very favourable sites would be strongly sought after and in consequence occupiers would pay a premium location value, marginal locations would have much lower payments.

One of the greatest benefits would be the increased freedom and opportunities that would become available as conventional taxes were reduced and replaced. Employment and trade would both become much more viable at the margin and this is likely to affect those regions which at present are the least prosperous. Reduced dependency on the state would be likely to reduce government expenditure. Without taxation of income the per capita employment costs of education, health and other labour-intensive services would reduce considerably.

These are particular improvements, but the overall effect of this policy would be to re-balance the economy. Present conditions, particularly in the UK with its heavy taxes on productive enterprise and low taxation on income from uplifts in property values encourage rent extraction and discourage the provision of wealth and services. Replacing taxation with payment of land rents would move in the opposite direction and mean that unearned income from property would be much less attractive and productive activity much more viable. This would rebalance the distribution of wealth, and so provide a holisitic way of addressing the many problems now identified with excessive inequality. In particular it would provide opportunities for greater earned prosperity for those now in the lowest portion of the income scale.

[1] Hugh Dalton, Principles of Public Finance, London: George Routledge & Sons, 1923, Part II, Chapter V.

[2] http://www.housing.gov.ie/environment/waste/plastic-bags/plastic-bag-levy accessed 30/12/2016

[3]http://www.econport.org/econport/request?page=web_experiments_modules_taxes_lecture#dwloss accessed 30/12/2016

[4] 2013/14 figures published June 2015. Figures relate to non-retired households.

http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160105160709/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_407906.pdf accessed 30/09/2016

[5] Ronald Burgess, Public Revenue Without Taxation, Shepheard-Walwyn, 1993.

[6] A similar distinction was also taken up by Liam Murphy and Thomas Nagel in their influential work on Tax Justice, The Myth of Ownership, Taxes and Justice, Oxford University Press, 2002, but applied to personal income rather than landed property.

[7] Alfred Marshall, Principles of Economics, Bk V Ch X, referred to in Burgess above.

[8] see for example: https://www.theguardian.com/public-leaders-network/2016/jul/12/developers-estate-agents-and-homeowners-cash-in-on-crossrail-london-elizabeth-line?CMP=share_btn_tw accessed 06/01/2017

[9] see for example: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/09/04/parents-face-premiums-of-up-to-630000–to-live-near-top-performi/ accessed 06/01/2016

Articles

Land Value Tax Links

The Tax Burden

Article List

- Welcome

- SA 88. Is there another way? by Tommas Graves

- SA 87. Time for a look at Rent by Tommas Graves

- SA 86. It’s rather Odd………….. By Tommas Graves

- SA85. Born to become a Georgist by Ole Lefmann

- SA84. Happy Nation by Lasse Anderson

- SA83. Ulm is buying up land, sent by Dirk Lohr

- SA82. Radical Tax Reform by Duncan Pickard

- SA 81. All taxes come out of Rents, by Rumplestatskin.

- SA 80. The Housing Crisis and the Common Good, by Joseph Milne

- SA 79. The “housing crisis” is no such thing, by Mark Wadsworth

- SA78. The Inquisitive Boy by “Spokeshave”

- SA 75. A Note on Swedish Taxes, by Tony Vickers MScIS MRICS

- SA 74. Homes Vic by Emily Sims

- SA73 Public Revenue Without Taxation by Peter Bowman

- SA71. Two presentations by Ed Dodson

- Short Sighted Benevolence

- SA 72. CAN YOU SEE THE CAT?

- SA70. Dissertation on Land Rental by Marion Ray

- Verses on the theme

- SA69. Argentina by Fernando Scornic Gerstein

- SA68. The Right to Work, by Leslie Blake

- SA66. The Most Wonderful Manuscript by Ivy Akeroyd 1932

- SA65. Housing Crisis? What Housing Crisis? by Mark Wadsworth

- SA64. Making Use of History by Roy Douglas

- SA63. The Fairhope Single Tax Colony – from their website

- TP35. What to do about “The just about managing” by Tommas Graves

- SA62. A Huge Extra Resource, by Ed Dodson

- SA61. Foundations of Earth Sharing Why It Matters: By Lawrence Bosek

- SA60. How to Restore Economic Growth, by Fred Foldvary, Ph.D.

- Two cartoons by Andrew MacLaren MP

- SA59. The Meaning of Work, by Joseph Milne

- SA 58. THE FUNCTION OF ECONOMICS, by Leon Maclaren

- SA 57. CONFUSIONS CONCERNING MONEY AND LAND by Shirley-Anne Hardy

- SA 56. AN INTRODUCTION TO CRAZY TAXATION – by Tommas Graves

- SA 55. LAND REFORM IN TAIWAN by Chen Cheng (preface) 1961

- SA54. Saving the Commons in an age of Plunder – by Bill Batt

- SA53.- Eurofail – VAT, by Henry Law

- SA52. Low Hanging Fruit – by Henry Law

- SA51. Location Theory and the European Union, – by Peter Holland

- SA50. Finland’s Basic Income – why it matters by Fred Foldvary, Ph.D.

- SA 29. A New Model of the Economy, by Brian Hodgkinson, as reviewed by Martin Adams of Progress.org

- Economics Explained (In 1 Simple Cartoon)

- SA 48. LANDED (Freeman’s Wood) by John Angus-StoreyG2

- SA 47. Justice and the Common Good by Joseph Milne

- SA 49.Prosper Australia – Vacancies Report

- SA39. A lesson from Alaska: further thoughts? By Alanna Hartzog

- SA23. Taxation: a brief history by Roy Douglas

- SA45. Of course, it wouldn’t solve all problems………by Tommas Graves

- SA43. TIME TO CALL THE LANDOWNERS’ BLUFF by Duncan Pickard

- SA44. Answering questions to UN Habitat 3 Financing Urban Development by Alanna Hartzog

- SA15. Why we don’t have a Housing Shortage, by Ben Weenen

- SA27. Money and Natural Law, By Tommas Graves

- SA42. NO DEBT, HIGH GROWTH, LOW TAX By Andrew Purves

- SA40. High Land Prices and Rural Unemployment, by Duncan Pickard

- SA28. Economics is a Natural Science by Duncan Pickard

- SA34. Economic Answers to Ecological Problems by Seymour Rauch

- SA22. Public Revenue without Taxation by David Triggs

- SA41. WHAT FAMOUS PEOPLE SAID ABOUT LAND contributed by Frank de Jong

- SA36. TAX THE RICH? Pikety and all that……..by Tommas Graves

- SA46. LAND VALUE TAX: A VIABLE ALTERNATIVE By Henry Law

- SA35. HOW CAN THE ECONOMY WORK FOR THE BENEFIT OF ALL? By Peter Bowman, lecture given at the School of Economic Science.

- SA38. WHO CARES ABOUT THE FAMILY by Ann Fennell.

- SA30. The Turning Tide: The Beginning of Monetary Trade in Anglo-Saxon England by Raymond Makewell

- SA31. FAULTS IN THE UK TAX SYSTEM

- SA33. HISTORY OF PUBLIC REVENUE WITHOUT TAXATION by John de Val

- SA32. Denmark By Ole Lefman

- SA25. Anglo-Saxon Land Tenure by Raymond Makewell

- SA21. China – Four Thousand Years of Taxing the Land by Peter Bowman

- SA26. The Economic Philosophy of Georgism, by Emma Crosby